In the ongoing and often heated discussion about the condition of modern education, opinions are rarely in short supply. Policymakers debate standards, administrators analyze performance data, and advocacy groups promote reforms aimed at reshaping classrooms from the ground up. Most of these conversations focus on systems, structures, and strategies.

Yet one voice, emerging not from a think tank but from years spent inside real classrooms, redirected the conversation toward a far more personal place: the home. That voice belonged to Lisa Roberson, a retired educator whose candid open letter ignited widespread discussion after it was published in the Augusta Chronicle. Her message challenged prevailing assumptions and placed responsibility where few expected it to land.

Roberson’s letter first appeared in 2017, yet its relevance has continued to grow. As education systems faced unprecedented disruption during global crises and rapid technological shifts, her observations remained strikingly consistent with what many teachers continue to experience.

She opened her letter with a sense of deep fatigue, expressing frustration with decisions made by individuals who, in her view, lacked recent classroom experience. For Roberson, the growing gap between policy discussions and everyday classroom realities had become impossible to ignore.

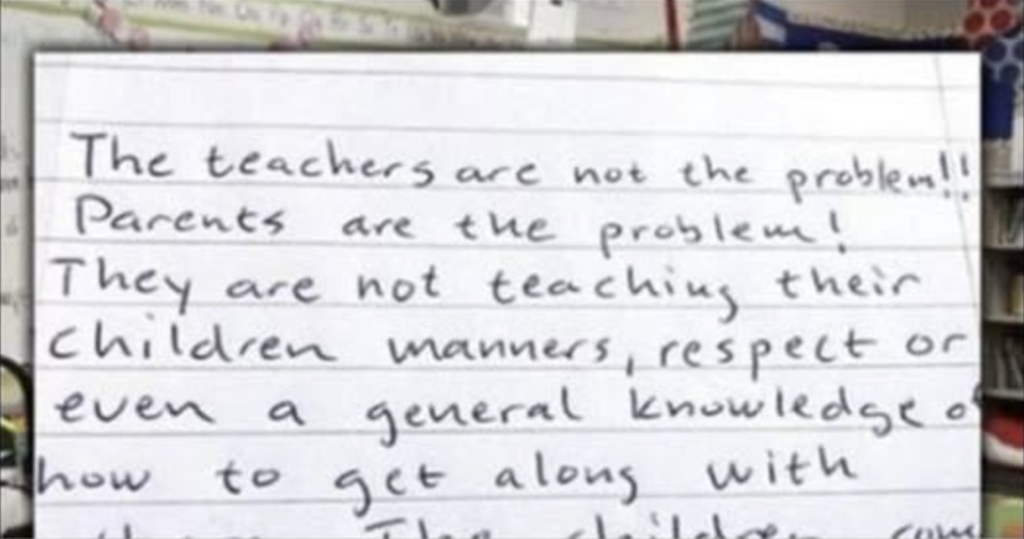

At the center of her argument was a firm assertion that unsettled many readers. Roberson rejected the idea that teaching methods or educator dedication were at the core of declining academic outcomes. Instead, she argued that the erosion of basic values taught at home had placed an unsustainable burden on schools.

According to her, teachers increasingly find themselves managing behavior, mediating conflicts, and teaching basic social skills before academic instruction can even begin. The classroom, once designed primarily for learning, has become a space where foundational life lessons are expected to be delivered alongside math and reading.

One of the most vivid points in Roberson’s letter focused on priorities within modern households. She described a recurring scene familiar to many educators: students arriving at school wearing expensive clothing or shoes, yet lacking essential learning materials.

Pencils, notebooks, and other basics were often missing, leaving teachers to cover the cost themselves. This contrast, she argued, reflected a deeper issue—not a lack of resources, but a misalignment of values. Appearance and status, in her view, had taken precedence over preparation and responsibility.

Roberson also questioned how success and failure in education are measured. She challenged critics who label schools as underperforming to look beyond test scores and examine parental involvement. Are parents attending meetings and school events? Are they responding to calls and messages from teachers? Are children arriving rested, fed, and ready to participate? These questions, she suggested, reveal far more about educational outcomes than standardized assessments ever could.

Her perspective reframed the idea of a “failing school” into something broader and more complex. Roberson argued that when students lack support, structure, and accountability at home, even the most skilled teacher faces an uphill struggle. Innovation, technology, and curriculum reform lose their impact when students are disengaged or disruptive. Education, she emphasized, is not a service delivered in isolation but a shared responsibility.

The response to her letter was swift and polarized. Many educators expressed relief, feeling that someone had finally articulated challenges they face daily but rarely feel permitted to voice publicly. They spoke of the emotional labor involved in teaching—roles that extend far beyond instruction into mentorship, discipline, and emotional support. Others, however, criticized Roberson’s stance, arguing that it overlooked socioeconomic realities. They pointed out that long work hours, financial stress, and limited access to resources can restrict parental involvement, even when intentions are strong.

Roberson did not attempt to offer a comprehensive solution to every social factor influencing education. Her letter was not a policy proposal but a call for accountability and reflection. She concluded by emphasizing that teachers cannot replace the role of parents. Without active participation from families, meaningful improvement remains out of reach.

Years later, her words continue to resonate because they touch on a fundamental truth. Education does not begin with lesson plans or technology upgrades. It begins with values, habits, and expectations formed long before a child enters a classroom. Governments can fund schools and revise curricula, but they cannot instill curiosity, discipline, or respect.

The enduring impact of Roberson’s letter lies in the conversations it sparked—around dinner tables, in teacher lounges, and among parents reflecting on their own roles. It reminds us that education thrives through partnership. When that balance shifts too far in one direction, the system strains under the weight. Roberson’s message remains a powerful reminder that the most influential classroom is often the home, and the most lasting lessons are taught through example, consistency, and care.